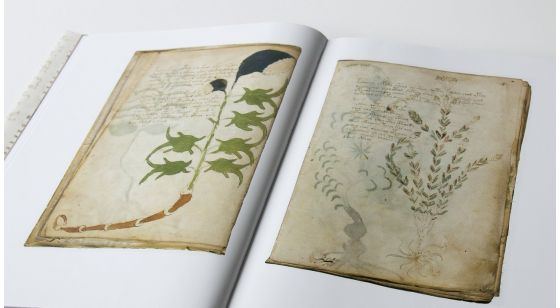

There are also no errors or corrections in the writing, which makes this book virtually unique among medieval manuscripts. The handwriting is steady and fluid, as if the creator didn’t have to halt and consult a codex, but knew the language by heart. The same words and phrases repeat over and over. Voynich-ese is tantalizingly similar to a real language. “They can’t figure out, is it another language? Is it Latin, is it German? But they also can’t tell if this is an invented language,” he says.Įven a group of World War II codebreakers couldn’t do it, although they did catalogue and classify “Voynich-ese,” the alphabet of 25 to 30 letters that seem to make up the book’s language.Ĭredit Davis Dunavin / WSHU A selection of 'Voynich-ese.' Translation unavailable. Still, Clemens says scholars haven’t had much luck trying to translate the mysterious text. “A lot of people thought that it was a hoax, that it was something done in the 20th century by Voynich himself,” says Ray Clemens, a curator at the Beinecke Library. The hoax idea was mostly put to rest when the book was carbon dated to the early 1400s, although occasionally a contrarian scholar will resurrect the claim. Names like Roger Bacon, John Dee and Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II were attached to it – either as owners or possible creators. Its journey from hand to hand was nearly as strange as its contents: at one point it passed from an alchemist to a Jesuit priest.

The odd little book was passed around privately for centuries.

#Voynich manuscript yale code#

In that case, the code may have been created to keep a medieval woman’s secrets about herbs, astrology and childbirth out of the hands of men. “I can see creating and creating and writing down.” “Honestly, upper-class women, not a lot to do all day,” she says.

Zyats speculates the book may have been written by a woman: the female forms are just a little too distinct and naturalistic. “Everybody loves the nude ladies in their interesting Dr. “And then there’s a section of the nude ladies,” Zyats says as she turns to the next page. The manuscript is not on public display and is generally only available for viewing by scholars, who must be approved by the library's curators and conservators.Īfter the plants, you start seeing pictures of astrological symbols and surreal landscapes. “Sometimes it seems as though the leaf of one goes with the root of another with the flowers of a third,” Zyats says.Ĭredit Davis Dunavin / WSHU Zyats flips through the Voynich Manuscript at the Beinecke Library and Rare Book Room. The weird thing is, none of the plants are real. Nothing out of the ordinary here – many medieval manuscripts cover herbalism, which was considered a medical art. The first pages show colorful, detailed illustrations of plants, flowers and herbs. Its pages are made of calfskin – an ordinary parchment for books in the Middle Ages. The book itself is about the size of a small paperback. “There’s a lot of beauty in this book, even though there’s a lot of crazy in it, too,” says Beinecke’s assistant chief conservator Paula Zyats as she flips through the Voynich manuscript. Now the book is about to receive its first official publication. The book has been hidden away in Yale University’s Beinecke Library since the 1960s, even as its notoriety has spread across pop culture. The Voynich Manuscript has baffled historians since it was brought to public attention over 100 years ago by its namesake, rare book collector Wilfrid Voynich. And it’s written entirely in an unknown language that’s stumped the world’s greatest codebreakers.

Its origins are unknown, its creator anonymous.

#Voynich manuscript yale full#

It’s one of the world’s great literary mysteries: a 15th century book full of bizarre illustrations of imaginary plants, astrological signs, surreal figures and landscapes.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)